Hidden Messages

Our choice of words often reveals more than we realize – for example, about whether we have experienced what we are talking about first-hand or not.

‘Mia stopped drinking coffee.’ A simple statement. And yet, this sentence can be used to communicate so much more. Not only do we learn that Mia does not currently drink coffee, but also that she used to drink coffee. Depending on who utters this sentence and how, it can also mean that the fact that Mia does not drink coffee might be a problem. Perhaps because there is only coffee in the house. Alternatively, it could be interpreted as Mia following a healthier lifestyle by giving up coffee.

“Up until some ten or 15 years ago, philosophical models of communication were still based on the assumption that communication involves exactly one speaker and one hearer. These models assume that the two would be perfectly rational and fully attentive, would strive to increase their shared knowledge, and would literally say what they mean. But this isn’t realistic,” believes Professor Kristina Liefke. She is Junior Professor of Philosophy of Information and Communication at Ruhr University Bochum.

Within the research unit “Constructing scenarios of the past: A new framework in episodic memory” (FOR 2812), Kristina Liefke and her colleagues are analyzing information that is indirectly communicated, but not directly expressed in a statement.

For the full article, visit RUB News

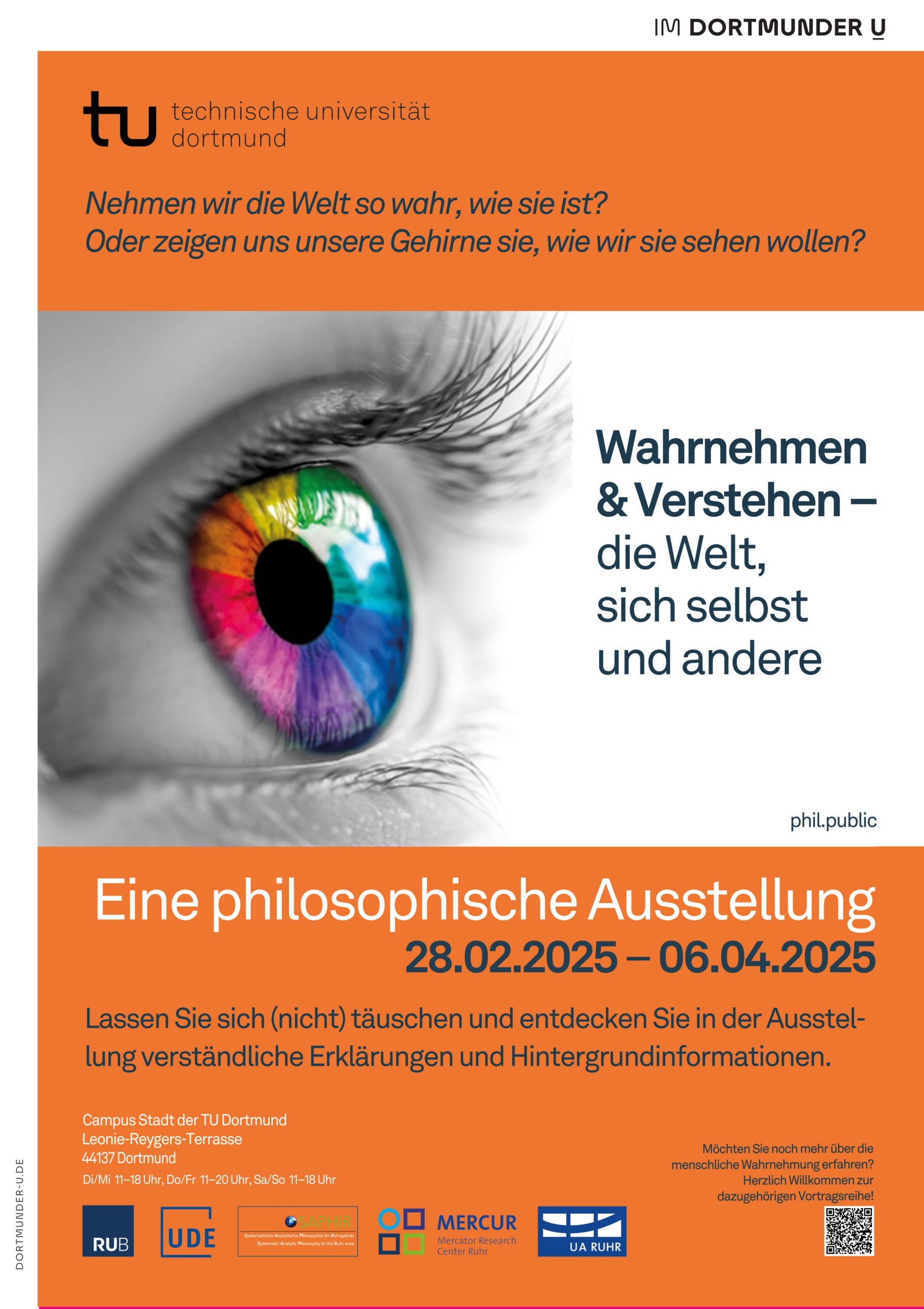

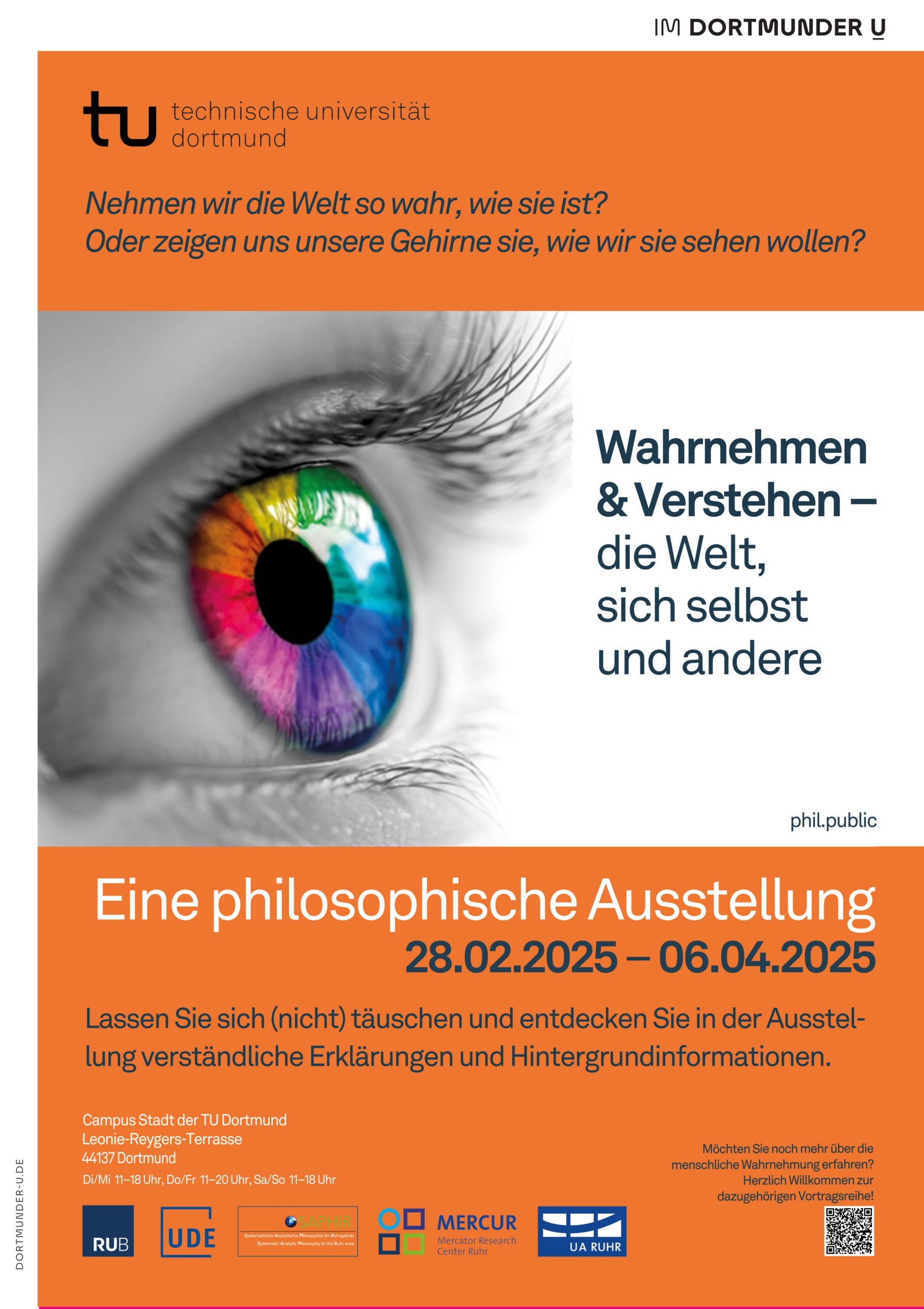

Wahrnehmen und Verstehen

Begleitend zu einer Ausstellung im Dortmunder U ist Albert Newen bei WDR 5 im philosophischen Radio zu Gast.

Wahrnehmungen sind das Fenster zur Welt – zu den Dingen in unserer Umgebung, zu anderen Menschen und auch zu uns selbst. Wir sehen, hören, riechen und ertasten unsere Welt. Nehmen wir diese so wahr, wie sie ist, oder eher so, wie wir sie haben wollen? In welchem Maße wird unsere Wahrnehmung im Alltag von Vorurteilen, Denkmustern und Vorwissen beeinflusst? Und welche Folgen hat dies für unser Verstehen der Welt? Wie wird unser Bild von der Welt und von uns selbst geprägt? Zu diesen Fragen spricht Moderator Jürgen Wiebicke mit Prof. Dr. Albert Newen von der Ruhr-Universität Bochum am 31. März 2025 von 19.04 Uhr bis 20 Uhr in der Sendung „Das philosophische Radio“ in WDR 5.

For full article & audio visit RUB News

Two Brain Areas Compete for Control

The locus coeruleus and the ventral tegmental area compete for control over the formation of memory content. This has been shown by a team of neuroscientists using light-controlled nerve cells.

Researchers at Ruhr University Bochum, Germany, have studied the impact of two brain areas on the nature of memory content. The team from the Department of Neurophysiology showed in rats how the so-called locus coeruleus and the ventral tegmental area permanently alter brain activity in the hippocampus region, which is crucial for the formation of memory. The two areas compete with each other for influence to determine, for example, in what way emotionally charged and meaningful experiences are stored. Dr. Hardy Hagena and Professor Denise Manahan-Vaughan conducted the study using optogenetics. In the process, they genetically modified rats so that certain nerve cells could be activated or deactivated with light. They published their findings in the journal PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences) on December 30, 2024.

For full article, see RUB News

Primary School Children Outperform All Other Age Groups

A learning experiment with participants of different ages produced surprising results.

The ability to make the connection between an event and its consequences – experts use the term associative learning – is a crucial skill for adapting to the environment. It has a huge impact on our mental health. A study by the Mental Health Research and Treatment Center (FBZ) at Ruhr University Bochum, Germany, shows that children of primary school age demonstrate the highest learning performance in this area. The results pave the way for a fresh perspective on associative learning disorders, which are linked to the development of mental illness later in life. The researchers published their findings in the journal Communications Psychology on December 16, 2024.

Until now, it was unclear how associative learning develops over different stages of life. This is why the team headed by Professor Silvia Schneider, Professor of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, and Dr. Carolin Konrad conducted the first systematic study of this ability in infants, children, adolescents and adults. In the study, test participants had to learn to react to a stimulus with a specific response.

For full article, visit RUB News

“Wahrnehmen & Verstehen – die Welt, sich selbst & andere”

“Perceiving & Understanding – the World, Oneself, & Others”

Forschende aus der Philosophie der drei Ruhrgebietsuniversitäten zeigen im Dortmunder U optische Täuschungen.

Vom 28. Februar bis zum 6. April 2025 können Gäste der Ausstellung „Wahrnehmen & Verstehen – die Welt, sich selbst und andere“ die faszinierenden Prozesse der menschlichen Wahrnehmung erkunden. Die Ausstellung auf der Hochschuletage des Dortmunder U wird vom MERCUR-geförderten Projekt „SAPHIR – Systematic Analytic Philosophy in the Ruhr Area“ unter Beteiligung der Philosophie-Institute der Ruhr-Universität Bochum (Albert Newen), der Technischen Universität Dortmund (Katja Crone) und Universität Duisburg-Essen (Raphael van Riel) organisiert.

https://www.wie-wir-die-welt-sehen.de

For full article, see RUB News

Rubin Special Edition “Extinction Learning” published

All about the work of the Collaborative Research Center 1280.

Do you know this too? You get a new PIN for your debit card, memorize it at home, but then stand in front of the ATM and all that comes to mind is your old PIN. This is because your brain still associates your old PIN with this place. Presumably a bearable problem if it’s only about withdrawing money. However, if you have learned to associate neutral experiences with fear and cannot get rid of it, this can have serious consequences. The reason is that relearning – also known as extinction learning – does not work properly.

The team from the Collaborative Research Center 1280 “Extinction Learning” investigates what happens in the brain during extinction learning, why context is crucial and what this means for overcoming fear and pain. The researchers report on their work in a special edition of the science magazine Rubin. It was published on January 7, 2025 and is available online.